Django Miceli

5/6/25

Opaque backgrounds, Vibrant clothing, Translucent colors, and Indigo trees

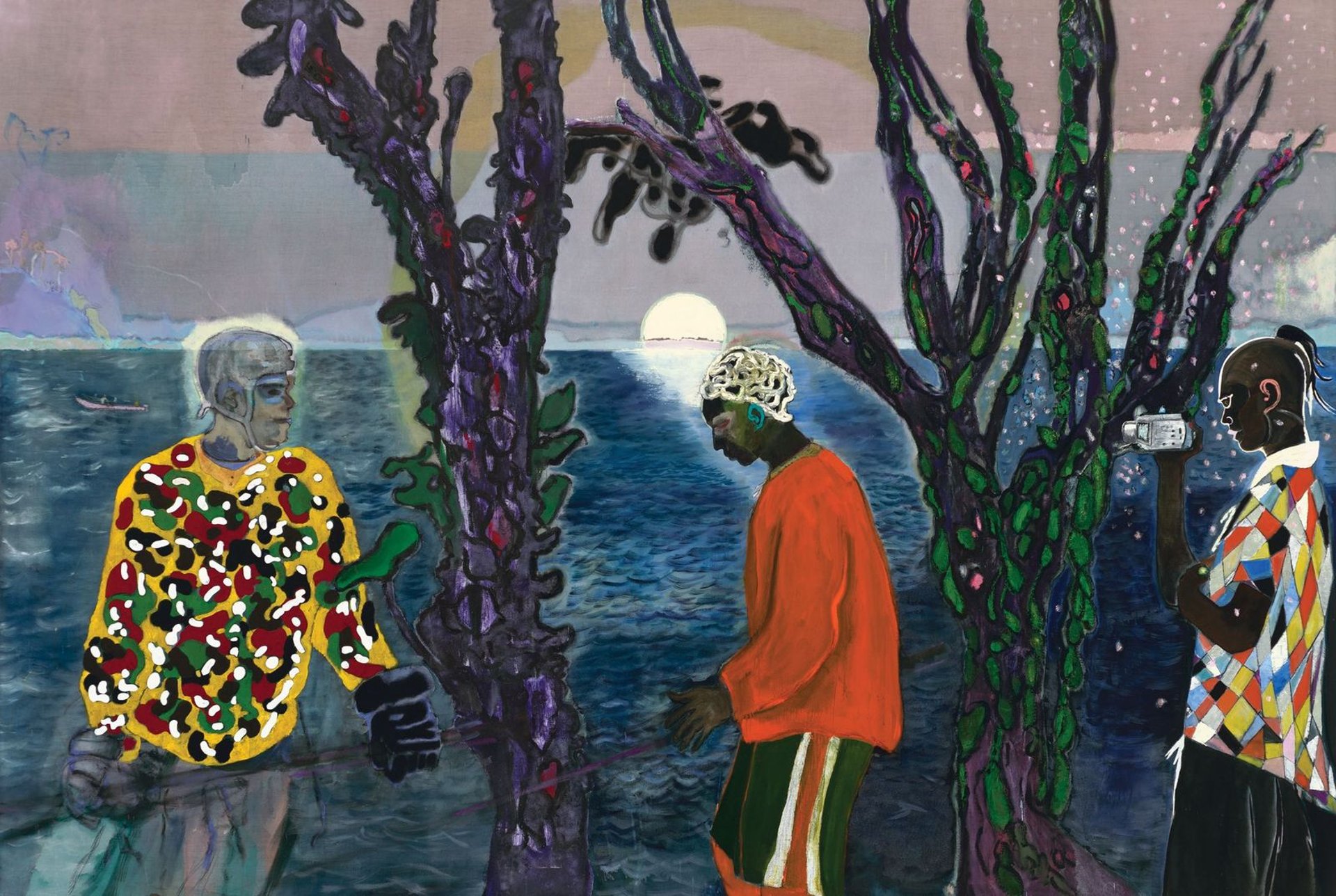

Figure 1: Peter Doig, Two Trees, 2017, oil on canvas, gifted to the Met.

Peter Doig’s Two Trees has many interesting colors. There’s a vibrant orange, a yellow jersey with red, green, black, and white splotches, there’s brown and peach colors, but the one color that most intrigues me is indigo. India, East Asia, and Peru are where indigo originates from, dating back 5,000 years ago in the form of dye. It came from dye-bearing Indigofera plants. It was a long debate whether Indigo was a color or just a dye. It wasn’t seen as a color until Newton said it was in 1672.

In Two Trees, indigo is used to color the trees and the water, which is fitting since the pigment is derived from a variety of plants. David Scott Kastan, in his book On Color, dedicates each chapter to the unique histories of different colors. In the chapter titled “Dy(e)ing for Indigo,” he talks about the unconventional process that was used to make indigo dye in Persia, of indigo, “A French traveller in Persia in the seventeenth century records that, ‘the Dyers of that Countrey make a most excellent blew dye,’ whose quality seems to depend upon a ‘Particular secret.’ As he writes, ‘They put no urine to it, using Dogs-turd instead of it, which they say makes the Indigo to stick better to the things that are dyed.’” What the traveller is referring to here is the mordant, a substance that makes the dye bind to the fabric. In many cases, urine was the mordant used, and the stench was enough to keep people away. Some places used even fouler-smelling modants. Needless to say, working on one of these plantations was not a pleasant job. Andrea Feeser, the author of Red, White, & Black Make Blue, writes about how, in the South Carolina environment, while adapting to indigo production, enslaved Africans were an indispensable resource because they were experts in cultivation and indigo dying techniques. Indigo became a large cash crop in South Carolina. The conditions of these indigo plantations were uninhabitable, as Kastan writes in “Dy(e)ing for Indigo,” “In 1775, the naturalist Bernard Romans, in his Concise Natural History of East and West Florida, warned that the site of indigo production ‘should always be remote from’ any living area ‘on account of the disagreeable effluvia of the rotten weed and the quantity of flies it draws.’” The enslaved Africans did not receive recognition, though it would not have been possible without them. Doig’s painting, Two Trees, also touches on similar issues. Many people in Trinidad have roots in Africa. The New York Times writer, Calvin Tomkins, writes, "Each figure in Doig’s painting thus gestures towards the tensions and dilemmas in reckoning with complex intertwined histories, spanning colonialism, to slavery in the Americas and its legacies." These are issues that Doig addresses through his unique position as a “privileged if perennial outsider,” Tomkins writes.

The use of indigo blue in Peter Doig’s Two Trees points to the violent history of the dye’s production. Tomkins highlights a quote from Peter Doig while talking about Two Trees: "At first, it was just the two trees…Looking through them, you’re looking straight toward Africa. You think about that journey across the ocean, where so many people here came from. The painting is not about that, but it’s in there. To me, the painting is about being complicit, being involved in something terrible." At first glance, violence is not the first thing that comes to mind when looking at the painting. You do not notice the tension between the figures right away. The ocean, the muted pink and yellow and grey in the sky, make a serene picture behind the figures. The way Doig renders nature with such enchanting colors, the leaves crawling up the trees are a luminous shade of green, and the trees themselves painted in a deep purple where the paint has been layered heavily, and where it hasn’t, a pale but bright shade of purple, distracts the viewer from the fact that the two trees are closing in on the center figure, just as the two figures with patterned shirts do. Once the violent themes this painting is erected from are realized, it is difficult not to feel deceived by the beauty of Doig’s palette. Whether intentional or not, Two Trees makes the viewer wonder what it takes to be complicit. Or it shows them at least how easy it is to watch and be involved in "something terrible.” The indigo blue of the ocean in Two Trees, and the view that is facing “straight toward Africa,” is reminiscent of the indigo blue plantations. Were the consumers of indigo dyed fabric ignorant or complicit in the atrocities it took to create the beautiful color?

In Kastan’s On Color “These ‘Sabians’ believed that the Jews, trying to prevent the baptism of Jesus, had ‘fetch’d a vaste quantity of Indigo … and flung it into Jordan,’ hoping to pollute the river; and as a result, God particularly Curs’d that Colour.” This refers to the dye that was cursed and not the indigo of the seven colors of the rainbow which Kastan says are “a gift from god.” The history of indigo dye is vast; on top of the history of slavery, it has roots in biblical mythology. Negative connotations wade over this dye, though it is so beautiful.

In an interview with Doig, Bijutsu Techo, and Midori Matsui, Doig says, “You have to realize that the abstraction of this kind goes back to Vélazquez and Pollock. I was inspired by such painters. I was not making reality, but a suggested reality. I was suggesting reality, not really trying to make anything that has to do with realism.” Doig captures his impression of reality while grappling with these heavy subject matters. Doig uses similar colors to Pollock and Vélazquez. This can be seen through the abstraction Doig takes on in his paintings. Doig even used a photograph of Jackson Pollock as inspiration for his painting Daytime Astronomy (Grasshopper). Regarding Vélazquez, Doig shares a similarity in his artistic approach. This way of painting is not done by attempting to soullessly mimic the world. Doig is painting how he sees the world, the way he depicts it, through his way of painting. It’s a suggested reality because it is painted based on the details that Doig wants to capture.

Figure 2: Photograph of Jackson Pollock.

Figure 3: Peter Doig, Daytime Astronomy (Grasshopper), 1998, oil on canvas, 118 by 144.8 cm. 46 1/2 by 57 in.

Doig lived in Trinidad and Canada, which present two very different settings and cultures of color. Trinidad is more vibrant, and Canada is more overcast. Peter Doig had a hillside home in Trinidad where he spent part of his youth and moved back to in the early 2000s. Two Trees was inspired by the view of his hilltop home. In Trinidad, colors are very bright. Here he is bringing the Caribbean into his painting. He makes the clothing especially bright in this painting, and the background he uses is a signature technique of his, where he thins out oil paint and makes it almost translucent. This gives the painting layers of color. Translucent thinned-out oil paint is a recurring technique of Peter Doig’s. Doig has a history of hockey; during his childhood in Canada, he played and was a committed fan. In the painting, the figure on the far left wears full hockey gear and a jersey, while the central figure seems to be the defender.

In Judith Nesbitt and Jonathan Watkins book of essays Days Like These Ben Tufnell writes in his essay, “Peter Doig” “His paintings sometimes depict actual places or autobiographical events, but more usually they represent a very personal combination of elements drawn from several sources, combined in such a way as to stimulate a memory or a sensation associated with a particular place or time.” The way Doig combines his personality and his past experiences into a painting that has multiple facets is unique. Stevenson, in his essay, “Peter Doig: No Foreign Lands,” writes similarly of Doig; Doig’s exposure to several different cities, such as London, New York, and Düsseldorf, impacted his painting and can be attributed to the “particularly rich visual knowledge and archive of motifs, which he draws from continually in his work.” Doig has a rich history and pulls from photographs he has captured throughout his life. His knowledge of art history lends him skills that can be traced back to many monumental visionaries. This puts him on par with artists like Pollock, Velázquez, and Munch.

Peter Doig’s color use is unique in the world of painting. In the past, authentic indigo dye has been used historically by painters to add a wash or tint to their canvas. This can be traced back to Ancient times: “In India, Indigo was used as a pigment on paper and in murals since at least 2000 BC.” It is unclear if Doig uses Indigo derived from the actual plant in his paintings. He wants the painting to come out how it comes out. He does not want a tight procedure; he wants spontaneity. Paul Bonaventura writes in a Burlington Magazine exhibition review, “His canvases look palpably finished yet they retain what might be described as a contingent quality, which keeps alive the possibility of change.” He believes painting would be boring with procedure. If he knew how the painting would turn out, it would not be a Peter Doig. He likes to work on multiple works at a time for long periods and come back to each one as he wishes. He will use crusty old paint from a jar and thinned-out oil paint instead of taking his paint straight from the tube. This allows for an unpredictable painting to emerge. In the painting Man Dressed as a Bat, Doig allowed it to be rained on from holes in his studio. He likes it when nature has an impact on his paintings, so this was not a problem for him. Instead, he saw it as a pleasant occurrence and went with it.

Figure 4: Peter Doig, Man Dressed as Bat, 2007, Oil on linen.

Calvin Tomkins mentions Edvard Munch, a painter who deeply inspired Doig. Doig’s use of color is comparable to Munch's. Doig layers many coats of paint onto his canvas, which makes colors shine through in unexpected ways. Doig uses earthy and muted tones, contrasted with warm oranges and vibrant reds. Doig’s paintings also relate to Munch’s by depicting deep emotion. The rest of the information Tomkins shares about Two Trees is about the figures and how Doig’s personal history is incorporated into the painting.

Doig also came out with a Dior fashion line for their Fall collection of 2021. The collection is color-matched by Doig, working closely with the designer to match his paintings. One sweater is a perfect match for the yellow sweater seen in Two Trees. On Doig’s instagram, he writes that the collaboration was “an honour and [a] thrilling experience to turn ideas and dreams into colour and functional forms." There were even indigo colored pieces in the collection. There is no confirmation about the use of real indigo dye for this collection. Indigo dye, derived from plants like Indigofera tinctoria, is occasionally used to color cotton yarn for denim production. It is more likely that Dior used synthetic indigo dye.

Figure 5: Peter Doig x Dior, Fall/Winter Collection, 2021.

Figure 6: Peter Doig x Dior, sweater, Fall/Winter Collection, 2021.

The colors are felt through human memory’s distortion of reality and cultural hybridity. They become emotional codes rather than descriptive facts. This is another way that Doig uses abstraction to create an image of the world he sees. He uses colors in a way that allows us to experience reality differently, perhaps allowing us to gain a new understanding of it. In Two Trees, the violence underlying the painting has to be taken in along with the peaceful horizon. It brings to mind the exploitation of humans that was integral to the creation of the commodity that was indigo dye. The abstraction of the violent scene in Two Trees is achieved largely by the use of color and helps us to experience what it’s like to be complicit in “something terrible.”

Works Cited:

Ben Trufnell, “Peter Doig,” in Days Like These: Tate Triennial Exhibition of Contemporary British Art 2003, ed. by Judith Nesbitt and Jonathan Watkins (London: Tate, 2003), 80-85.

David Kastan and Stephen Farthing, “Dy(e)ing for indigo,” in On Color, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 119-135.

Andrea Feeser, Red, White, & Black Make Blue: Indigo in the Fabric of Colonial South Carolina Life, (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013), 73-84.

Paul Bonaventura, “Peter Doig. London.” The Burlington Magazine, 2008, 150, no. 1261: 274–75.

Robert Louis Stevenson, "Peter Doig: No Foreign Lands." Queen's Quarterly 121, no. 1(Gale Literature Resource Center, 2014), 114.

Bijutsu Techo and Midori Matsui, “I Am Never Bored with Painting: Peter Doig, Interview.” Michealwerner.com, 2020.

Peter Doig, Instagram, 2021.

Calvin Tomkins, "The Mythical Stories in Peter Doig’s Paintings," Newyorker.com, 2017.

Evie Hatch, “Indigo: The Story of Blue Gold,” Jacksonsart.com, 2025.